My grandmother often refers me as the “lucky one”. I did not understand while I was a kid nor curious about that. After all, my grandmother was just a patriarchal fudge old lady in my perception while I was young. She does many things that no one would do, such as eating food even if it rots, never go to some places because she believes ghosts haunts there.

One day, randomly, my father started talking about my grandmother’s past of being a women community leader. That really caught my attention and sparked curiosity. That was unimaginable - my grandmother leading feminist movements and defending women’s rights in the village. In my mind she worshiped men akin to some religion. She seemed absolutely patriarchal to me.

I started to look into my grandmother’s past - something so close yet so far to me. I discovered that she experienced every feminist movement in the modern history of China. Among other things she had a courage to get a divorce while the society still considered it as a taboo.

This research led me into confusion: as liberated as she was, why was the grip of the patriarchal ideology still so unrelenting?

I recalled she called me the “lucky one” . I finally decided to ask her what does it really mean. “you got to live as a second daughter” she exclaimed and refused to say more. I still did not understand. I looked for answers through history, yet nothing seemed related.

One day, as I researched through local history of my city, I stumbled upon the keyword -famine.

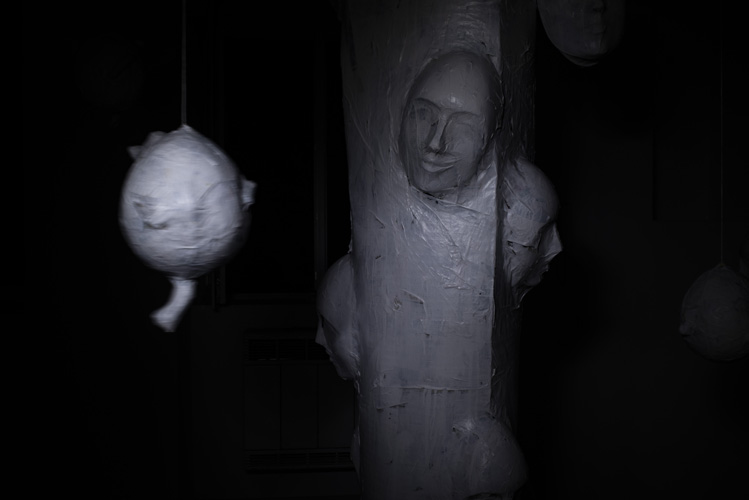

My subtle, early memories awoke relating to newly discovered facts how my city suffered famine for 300 years. Stories were whispered in my childish presence yet never meant for me: the woods of baby cries; a bamboo dustpan wrap around a dead body to stop soul from reincarnation; the female infant dead in the urinal.

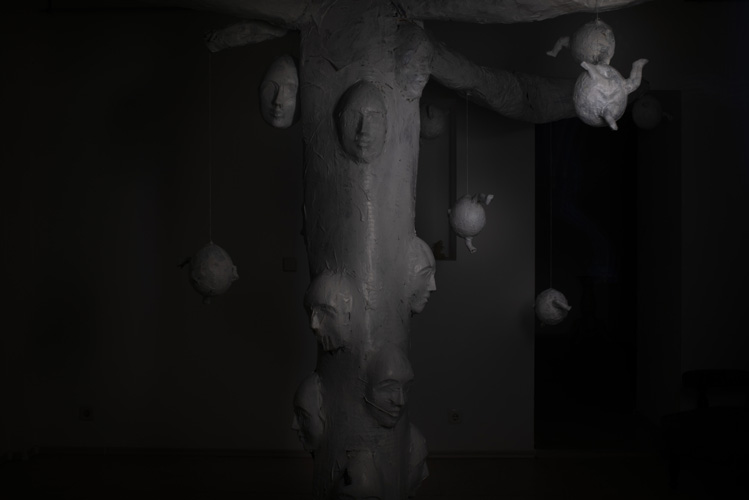

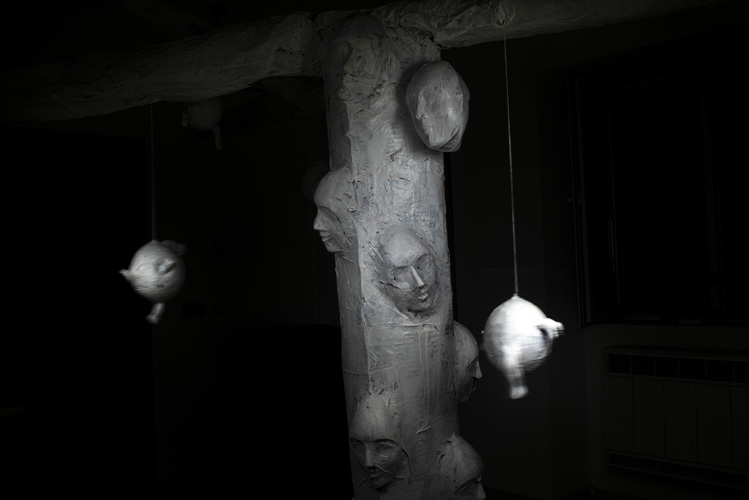

Finally, I patched a full story of my luck: The famine forced a triage for the living, and female creature was the bottom within the patriarchal hierarchy, the chosen sacrifice. The death leaves scarce traces of the previous existences. The shame of the perpetrators disconnected and severed the suffering and pain from the collective memory. Yet, the crimes remained unspoken, in whispers, prayers and body language of my grandmother. She might have witnessed it or, through tales of her ancestors, had the postmemory of it. The patriarchal mind inside her is her generational trauma.

The political feminist movement fail to emancipate and absolve her as this part of the history was erased, disabling mourning - public or private. Without mourning there’s no transformation. She was frozen in the patriarchal limbo just like female infants killed in the woods— the body got destroyed, the soul has been sealed and fail to reincarnate.

When there is no grave, we are condemned to go on mourning.

Can I make a grave for those untraceable and dead? Can my art be transformation for those unspoken and traceless brutalities? Can it crack or break the prison walls of our generational trauma? I am “lucky one” and I do try.

One day, randomly, my father started talking about my grandmother’s past of being a women community leader. That really caught my attention and sparked curiosity. That was unimaginable - my grandmother leading feminist movements and defending women’s rights in the village. In my mind she worshiped men akin to some religion. She seemed absolutely patriarchal to me.

I started to look into my grandmother’s past - something so close yet so far to me. I discovered that she experienced every feminist movement in the modern history of China. Among other things she had a courage to get a divorce while the society still considered it as a taboo.

This research led me into confusion: as liberated as she was, why was the grip of the patriarchal ideology still so unrelenting?

I recalled she called me the “lucky one” . I finally decided to ask her what does it really mean. “you got to live as a second daughter” she exclaimed and refused to say more. I still did not understand. I looked for answers through history, yet nothing seemed related.

One day, as I researched through local history of my city, I stumbled upon the keyword -famine.

My subtle, early memories awoke relating to newly discovered facts how my city suffered famine for 300 years. Stories were whispered in my childish presence yet never meant for me: the woods of baby cries; a bamboo dustpan wrap around a dead body to stop soul from reincarnation; the female infant dead in the urinal.

Finally, I patched a full story of my luck: The famine forced a triage for the living, and female creature was the bottom within the patriarchal hierarchy, the chosen sacrifice. The death leaves scarce traces of the previous existences. The shame of the perpetrators disconnected and severed the suffering and pain from the collective memory. Yet, the crimes remained unspoken, in whispers, prayers and body language of my grandmother. She might have witnessed it or, through tales of her ancestors, had the postmemory of it. The patriarchal mind inside her is her generational trauma.

The political feminist movement fail to emancipate and absolve her as this part of the history was erased, disabling mourning - public or private. Without mourning there’s no transformation. She was frozen in the patriarchal limbo just like female infants killed in the woods— the body got destroyed, the soul has been sealed and fail to reincarnate.

When there is no grave, we are condemned to go on mourning.

Can I make a grave for those untraceable and dead? Can my art be transformation for those unspoken and traceless brutalities? Can it crack or break the prison walls of our generational trauma? I am “lucky one” and I do try.